The Story of Lancelot and Galehaut

Galehaut is the first great tragic figure in French literature . . . His tale is at the heart of our new retelling of the medieval narrative.

Alongside the deeply resonant love story of Sir Lancelot and King Arthur's wife, Queen Guenevere, the "Book of Galehaut" tells us that Lancelot's extraordinary prowess and physical beauty inspired the love of Arthur's powerful foe, Galehaut, Lord of the Distant Isles. This modern adaptation of the thirteenth-century French Prose Lancelot recounts the vicissitudes of their friendship against the background of the far-better known tale of royal adultery. Galehaut is the first great tragic figure in French literature and the sole such character in the entire Arthurian legend. His tale is at the heart of our new retelling of the medieval narrative.

. . . ill-fated adulterers, whose irresistible love led not only themselves but in fact their entire world to perdition.

The story of Lancelot and Guenevere has had enduring appeal ever since it was invented in the twelfth century by the French writer Chrétien de Troyes. The protagonists early became a very model of ill-fated adulterers, whose irresistible love led not only themselves but in fact their entire world to perdition. The tale has been told and retold over the years in many languages and forms, but the most provocative and elaborate version is in the immense suite of early-thirteenth-century French narratives collectively called the Lancelot-Grail or Arthurian Vulgate Cycle. Related in this ensemble is the whole wondrous, adventure-filled, mythic history of Arthur and his chivalric kingdom.

. . . expanded the triangle Arthur-Guenevere-Lancelot into a rectangle, adding a figure named Galehaut, Lord of the Distant Isles, a powerful political and military foe to Arthur and a rival to Guenevere for the love of Lancelot.

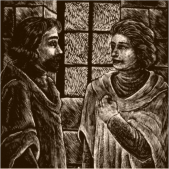

The anonymous author of the massive section devoted to Lancelot expanded the triangle Arthur-Guenevere-Lancelot into a rectangle, adding a figure named Galehaut, Lord of the Distant Isles, a powerful political and military foe to Arthur and a rival to Guenevere for the love of Lancelot. This second, overlapping love story, is an extraordinary tale, related with an understanding of human desires and aspirations unprecedented in its depth and richness. For love of Lancelot, Galehaut surrenders his political ambitions, voluntarily submitting to the rule of Arthur; the same love leads him to facilitate the rapprochement of Lancelot and the Queen. The invincible Lord of the Distant Isles, who had seemed destined to conquer the world, becomes a paragon of love-inspired self-sacrifice.

. . . later retellings of the Lancelot story, . . . show little or no interest in Galehaut.

Whether for political reasons or out of aversion to the homoerotic, later retellings of the Lancelot story, in whatever language, show little or no interest in Galehaut. This is especially true of Malory's great English treatment of the Arthurian legend in the fifteenth century, in which the "high prince" Galehaut appears but only peripherally and with no significant tie to Lancelot.

Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles . . . rescues from oblivion this all-important double love-story.

Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles, or the Book of Galehaut Retold is a work of restoration. From the mass of diverse detail and labyrinthine complications of the medieval Lancelot-Grail Cycle, it abstracts the all-important double love-story and rescues from oblivion the first truly tragic figure in French literature.

— Samuel N. Rosenberg

The Retelling:

Patricia Terry explains

We both felt that a great love story had been lost to the world.

There may be a certain magic in the beginning of a project. In 1998, at a meeting of medievalists, I mentioned to Samuel Rosenberg my long-held desire to create a version in modern English of the story of Galehaut, the Lord of the Distant Isles. Saying this took some courage on my part since Professor Rosenberg had recently published, along with several other scholars, a complete, five-volume translation of the entire Lancelot-Graal, an anonymous early-thirteenth-century series of prose romances, including the Lancelot, concerning the rise and fall of the Arthurian kingdom. He himself had translated precisely that part of the cycle which interested me. Expecting him to follow the tendency of specialists to protect the letter of their texts, I was most happily surprised when he expressed unqualified enthusiasm for a retelling. We both felt that a great love story had been lost to the world, and ultimately he agreed to join me in trying to restore it.

. . . finding language that could bring the Galehaut story itself without distortion into the experience of present-day readers.

Our first task was to separate the story of Galehaut's ill-fated love for Lancelot from the labyrinthine plot in which it is contained. This was also the first test of our collaboration, since there had to be mutual agreement about which aspects of the tale were essential, which less so, which calling for justifiable elaboration, and so on. Many remarkable characters, impressive speeches, magical episodes had to be excluded. Beyond those decisions lay the whole challenge of finding language that could bring the Galehaut story itself without distortion into the experience of present-day readers. Sometimes this was a matter of the translation of key phrases. When Lancelot sets out for his first knightly adventures, he goes to say farewell to the queen who responds with the conventional phrase "biaux doux amis," which he takes literally as an expression of genuine affection. "Dear friend" should accommodate both possibilities. This translation eliminates a redundancy in the French, biaux and doux both more or less meaning "dear," a change characteristic of a general difference between Old French prose and our English. Sometimes, however, we adopted certain stylistic devices characteristic of the Old French tale and incorporable into modern English narration, most notably the occasional use of "emergent discourse," in which a character's speech suddenly breaks into the narrator's prose with no hint of speech save quotation marks.

. . . a narrative conceived to highlight the special, long-overlooked friendship of Lancelot and Galehaut.

In general, our version of the tale eliminates redundancy in language, proliferation of incident and character, and the medieval author's very leisurely manner, natural in thirteenth-century French but unwieldy in modern English. It would, moreover, have been distracting in a narrative conceived to highlight the special, long-overlooked friendship of Lancelot and Galehaut. Underneath the profusion of the medieval tale there is a profoundly moving and important story that demanded to be brought to light for a whole new modern readership. We hope we have done it justice in Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles.